Secret miracle

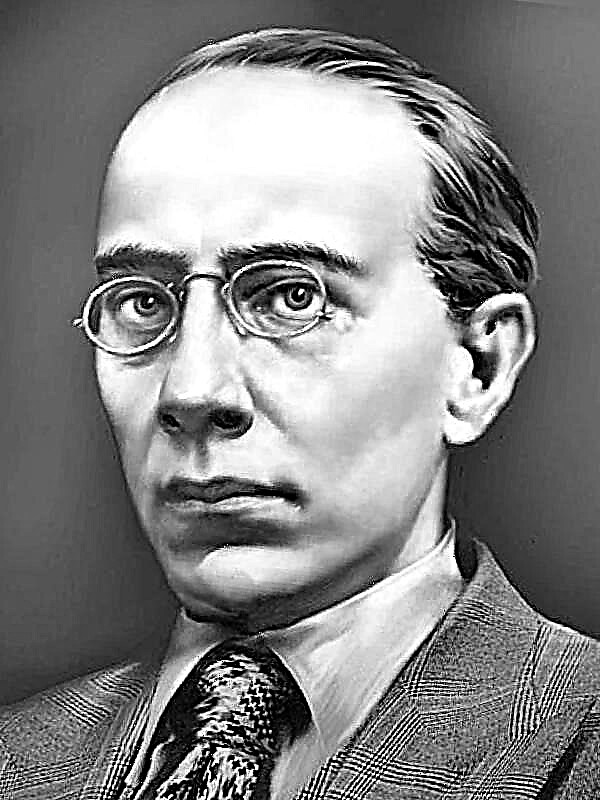

On the night of March 14, 1936, in the apartment on Tseletnaya Street, in Prague, Jaromir Hladik, the author of the unfinished tragedy “Enemies”, the work “Justification of Eternity” and the study of the implicit Judaist sources of Jacob Böhme, sees in a dream a long chess game. The game was started many centuries ago and was played between two noble families. Nobody remembered the prize amounts, but it was fabulously great. In a dream, Jaromir was the firstborn in one of the rival families. The clock marked every move made in battle. He ran under the rain in the sands of the desert and could not remember the rules of the game. Waking up, Jaromir hears a measured mechanical rumble. It was at dawn in Prague that the advance detachments of the armored units of the Third Reich entered.

After a few days, authorities receive a denunciation and detain Hladik. He cannot refute any of the Gestapo accusations: Jewish blood flows in his veins, the work on Boehme is pro-Jewish, he signed a protest against the Anschluss. Julius Rothe, one of the military ranks in whose hands is the fate of Hladik, decides to shoot him. The execution is scheduled for nine in the morning of March 29th - with this postponement, the authorities want to demonstrate their impartiality.

Hladik is horrified. At first it seems to him that the gallows or the guillotine would not be so scary. He continuously loses the upcoming event in his mind and dies a hundred times a day long before the appointed time, presenting the scene of his own execution in various Prague courtyards, and the number of soldiers changes every time, and shoot him from afar, then point-blank. Following the miserable magic - to imagine the cruel details of the future in order to prevent them from coming true - he eventually begins to fear that his inventions would not be prophetic. Sometimes he looks forward to being shot, wanting to put an end to the futile game of imagination. On the evening before the execution, he recalls his unfinished poetic drama "Enemies".

The drama respected the unity of time, place and action, it was played out in the Hradcany, in the library of Baron Remerstadt, one evening at the end of the 19th century. In the first act, Remerstadt is visited by an unknown. (The clock strikes seven, the sun sets, the wind carries the Hungarian fire melody.) This visitor is followed by others unknown to Remerstadt, but their faces seem familiar to him, he already saw them, possibly in a dream. The Baron becomes aware that a conspiracy has been drawn up against him. He manages to prevent intrigue. We are talking about his bride, Julia de Weidenau and about Yaroslav Kubin, who once bothered her with his love. Now he is crazy and imagines himself Remerstadt ... Dangers are multiplying, and Remerstadt in the second act has to kill one of the conspirators. The last action begins; the number of inconsistencies multiplies; the characters are returning, whose role, it seemed, has been exhausted: among them the murdered one flashes. The evening does not come; the clock strikes seven, the sunset reflects in the windows, a Hungarian fire melody sounds in the air. The first visitor appears and repeats his cue, Remerstadt answers him without surprise; the viewer understands that Remerstadt is an unfortunate Yaroslav Kubin. There is no drama: this is again and again the returning nonsense that Kubin constantly resurrects in his memory ...

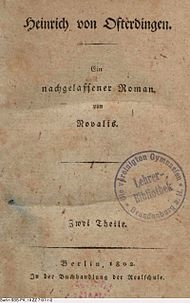

Hladik completed the first act and one of the scenes of the third: the poetic form of the play allows him to constantly edit the text without resorting to the manuscript. On the eve of the imminent death, Hladik turns to God with a request to give him another year to finish the drama, which will justify his existence. Ten minutes later he falls asleep. At dawn he had a dream: he must find God in one of the letters on one of the pages of one of the four hundred thousand volumes of the library, as the blind librarian explains to him. With sudden confidence, Hladik touches one of the letters on the map of India in the atlas that appears next to him and hears a voice: "You have been given time for your work." Hladik wakes up.

Two soldiers appear, escorting him to the patio. Fifteen minutes remain before the execution, scheduled for nine hours. Hladik sits down on a woodpile, the sergeant offers him a cigarette, and Hladik takes it and lights it, although he has not smoked until then. He unsuccessfully tries to recall the appearance of a woman whose features are reflected in Julia de Weidenau. Soldiers are being built in a square, Hladik expects shots. A drop of rain falls on his temple and slowly rolls down his cheek. The words of the team are heard.

And then the world freezes. The rifles are aimed at Hladik, but people remain motionless. The hand of the sergeant who gave the command freezes. Hladik wants to shout, but he cannot and understands that he is paralyzed. It does not immediately become clear to him what happened.

He asked God for a year to complete his work: the almighty gave him this year. God performed a secret miracle for him: a German bullet would kill him at the appointed time, but a year would pass from his team to his brain. Hladik's amazement gives way to gratitude. He begins to finish his drama, changing, shortening and redoing the text. Everything is ready, just one epithet is missing. Hladik finds him: a raindrop begins to glide over his cheek. There is a volley of four rifles, Hladik manages to shout something inaudible and falls.

Jaromir Hladik died on the morning of March twenty-ninth at ten o'clock two minutes.

South

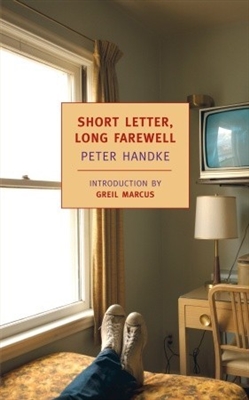

Buenos Aires, 1939. Juan Dahlmann serves as secretary in the Municipal Library on Córdoba Street. In late February, an unexpected incident happened to him. On that day, a rare edition of Thousand and One Nights in Weil’s translation fell into his hands; hurrying to consider his purchase, he, without waiting for the elevator, runs up the stairs. In the dark, something touches his forehead - a bird, a bat? The woman who opened the door to Dahlmann screams in horror, and, running a hand over his forehead, he sees blood. He cut himself on the sharp edge of the door just painted, which was left open. At dawn, Dahlmann wakes up, he is tormented by fever, and illustrations for "One Thousand and One Nights" interfere with a nightmare. Eight days stretch like eight centuries, the surrounding seems to Dahlmann hell, Then he is taken to a hospital. On the way, Dahlmann decides that there, in another place, he will be able to sleep peacefully. As soon as they arrive at the hospital, they undress him, shave his head, screw him to the couch, and the masked man puts a needle into his hand. Waking up with bouts of nausea, bandaged, he realizes that until now he was only in anticipation of hell, Dahlmann stoically endures painful procedures, but cries out of self-pity, learning that he almost died from blood poisoning. After some time, the surgeon tells Dahlmann that he can soon go to a manor for treatment - an old long pink house in the South, which he inherited from his ancestors. The promised day is coming. Dahlmann rides in a hired carriage to the station, feeling happiness and lightheadedness. There is time before the train, and Dahlmann spends it in a cafe for a cup of coffee forbidden in the hospital, stroking a huge black cat.

The train stands at the penultimate platform. Dahlmann picks up an almost empty wagon, throws the suitcase into the net, leaving himself a book to read, A Thousand and One Nights. He took this book with him not without hesitation, and the decision itself, as it seems to him, serves as a sign that misfortunes have passed. He tries to read, but in vain - this morning and existence itself turn out to be no less a miracle than the tales of Shahrazada.

“Tomorrow I will wake up at the manor,” Dahlmann thinks. He feels himself at the same time as if by two people: one moves forward on this autumn day and familiar places, and the other suffers humiliating resentments, being in a well-designed bondage. The evening is drawing near. Dahlmann feels his complete loneliness, and sometimes it seems to him that he travels not only to the South, but also to the past. He is distracted from these thoughts by the controller, who, having checked the ticket, warns that the train will stop not at the station that Dahlmann needs, but at the previous one, barely familiar to him. Dahlmann gets off the train almost in the middle of the field. There is no crew here, and the station manager advises hiring him in a shop one kilometer from the railway. Dahlmann walks slowly to the bench to extend the pleasure of the walk. The owner of the shop seems familiar to him, but then he realizes that he just looks like one of the employees of the hospital. The landlord promises to lay a chaise, and in order to pass the time, Dahlmann decides to have dinner here. At one of the tables guys are noisy eating and drinking. On the floor, leaning against the counter, sits a dark-skinned old man in a poncho, who seemed to Dahlmann the embodiment of the South. Dahlmann eats while drinking dinner with tart red wine. Suddenly, something light hits his cheek. It turns out to be a crumb ball. Dahlmann is at a loss, he decides to pretend that nothing happened, but after a few minutes another ball hits him, and the guys at the table begin to laugh. Dahlmann decides to leave and not allow himself to be drawn into a fight, especially since he has not yet recovered. The owner reassures him in alarm, calling at the same time by name - "Senior Dahlmann." This only worsens the matter - until now it was possible to think that the stupid trick of the guys hurt a random person, but now it turns out that this is an attack against him personally.

Dahlmann turns to the guys and asks what they need. One of them, not ceasing to shower with curses and insults, throws up and catches a knife and causes Dahlmann to fight. The owner says that Dahlmann is unarmed. But at that moment, an old gaucho sitting in a corner throws a dagger under his feet. As if the South itself decides that Dahlmann must fight. Bending down for a dagger, he realizes that a weapon that he almost does not possess will serve not as protection for him, but as an excuse for his killer. “They wouldn’t have been allowed in the hospital to have something like this happen to me,” he thinks, and after the guy goes out into the yard. Crossing the threshold, Dahlmann feels that to die in a knife fight in the open air, instantly, would be for him deliverance and happiness that first night in the hospital. And if he could then choose or invent death for himself, he would choose just that.

And, clutching the knife tightly, Dahlmann follows the guy.

Nutcracker

Nutcracker